that way in order to protect the

traditional family recipes, she said.

The would-be expansion in a year’s

time would necessitate the addition

of more machinery and more

personnel, but she said a project of

that scale would not be something

that could easily be copied.

Within five years, she’s expecting a

more sizable international presence

– and a significant volume increase

for the cocoa butter product in

particular.

“The growth is only due to

the demand,” she said. “There is

a demand locally and there is a

demand internationally, and we want

to be able to fit that demand. People are requesting the

product out there and we want to get it out there. The

quality is really great.

“A year ago it was a project. And I’m happy to

say that the project has evolved into the business.”

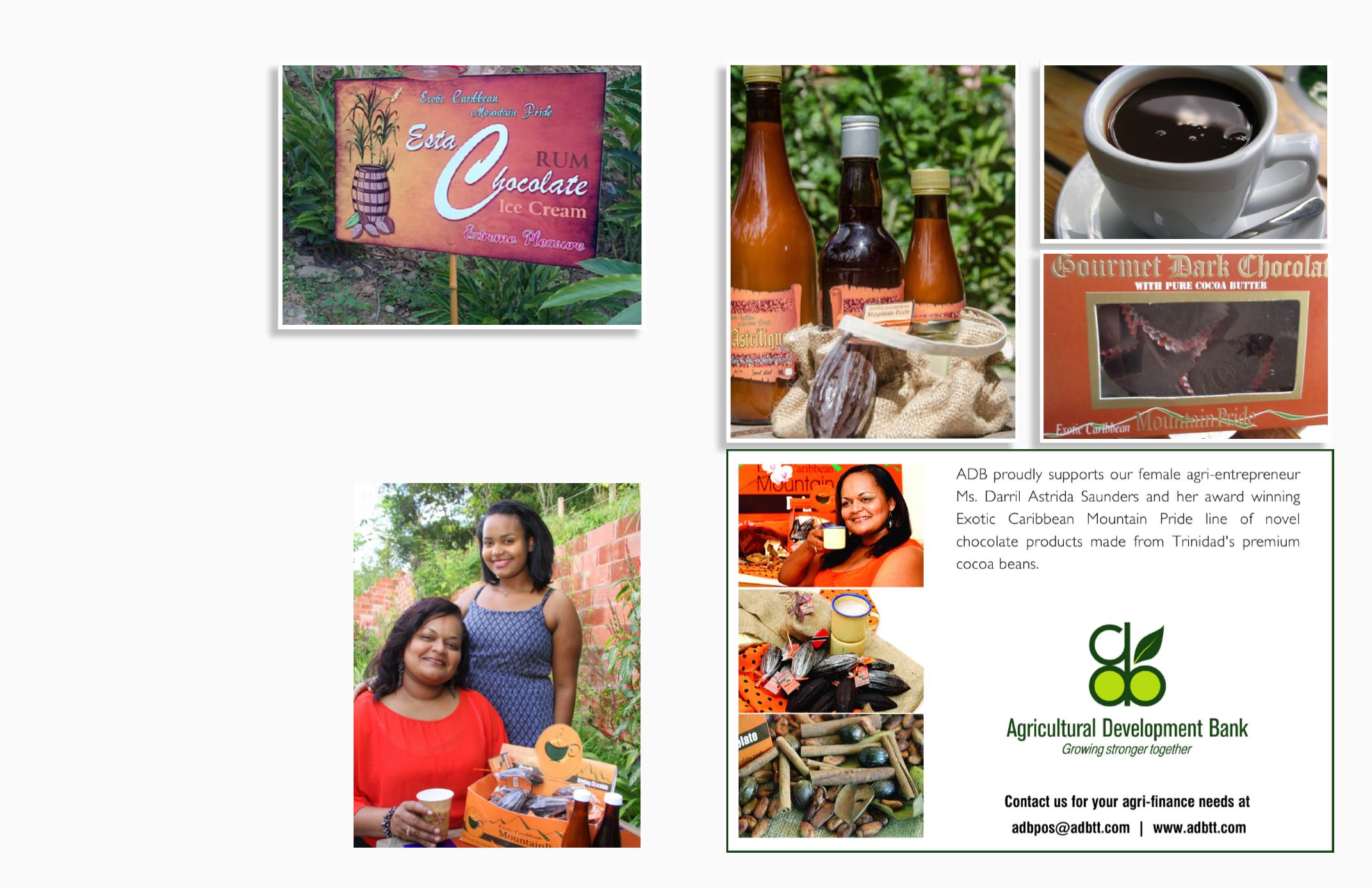

The family began by reaching back into the estate’s

history to restart a chocolate-making tradition that had

begun among the estate’s slave labor population. The

chocolate made by the slaves had never been sold as

a commercial product and it was no longer available in

the local market.

“There were not many people locally that were

doing anything with cocoa beans at that time,” Saunders

said. “We were one of the pioneers into trying to get

something more from cocoa than selling and exporting

the beans.”

The business initially sold the chocolates – shaped in

the form of a cocoa pod or fruit – to local souvenir

shops. It was a home-based souvenir business at first,

but the buzz surrounding the products soon grew

and ultimately drew the interest of local supermarkets

interested in getting involved.

Various ministries soon got word of the products as

well, which prompted orders from the government

to have the products available for island-based events

such as conferences and trade shows.

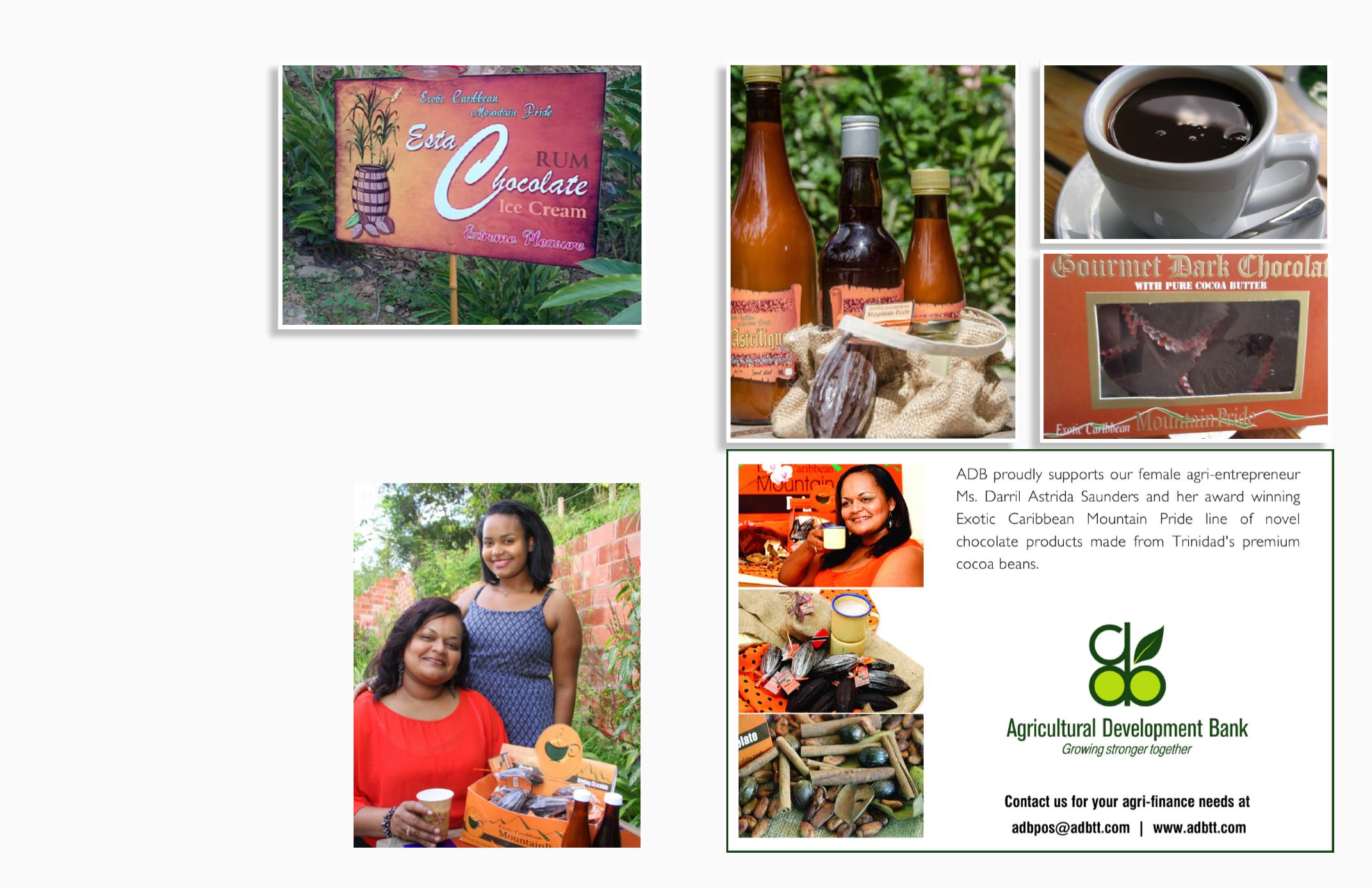

“Itwas almost immediate that the traditional chocolate

became an item,” Saunders said. “I was a bit surprised,

because it started off as just sort of a hobby to earn

some extra income. And it has turned into a business.

It has grown beyond the hobby stage.”