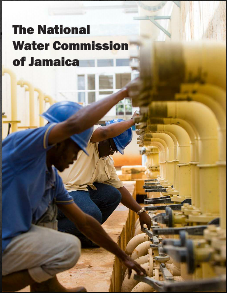

The National Water Commission of Jamaica

Serving you in so many ways

Business View Caribbean profiles The National Water Commission of Jamaica , the main provider of potable water supply in Jamaica.

The National Water Commission (NWC) was formally established in 1980, under the auspices of the National Water Commission Act. “Prior to 1980, there were two main organizations responsible for the provision of water supplies and sewage services throughout the island,” explains Mark Barnett, the NWC’s President since 2015, “the Kingston and St. Andrew Water Commission and the more rurally focused, National Water Authority. In 1980, there was an amalgamation of the two entities to form the National Water Commission.”

While it is not the only service provider in the country – there are a few private and quasi-governmental operations ongoing – the National Water Commission is charged with the responsibility of being the main provider of potable water supply, and the collection, treatment and disposal of wastewater services to the people of Jamaica. Today, the National Water Commission of Jamaica produces more than 90 percent of the country’s potable water from a network of more than 160 underground wells, over 116 river sources (via water treatment plants), and 147 springs. It produces 180,000 imperial gallons of potable water a day for over two million persons and supplies more than a half million of those persons with wastewater services, as well. Approximately 73 percent of Jamaica’s population is supplied via house connections from the National Water Commission and the remaining 27 percent obtains water from standpipes, water trucks, wayside tanks, community catchment tanks, rainwater catchment tanks, and direct access to rivers and streams.

Approximately 30 percent of Jamaica’s population is served by sewerage facilities operated by the National Water Commission of Jamaica. This includes some small sewerage systems, utilizing package plants, which are associated with housing developments in various locations throughout the country. The disposal of the sewage generated in the remainder of the population is done through various types of on-site systems such as septic tanks, soak-away pits, tile fields and pit latrines, or other systems operated by other entities.

The NWC operates more than 1,000 water supply, and over 100 sewerage facilities, islandwide. These vary from large raw water storage reservoirs at Hermitage and Mona in St. Andrew and the Great River treatment plant in St. James, to medium sized and small diesel-driven pumping installations serving rural towns and villages across Jamaica. The National Water Commission of Jamaica facilities also include over 10,000 kilometers of pipelines and more than 1,000 kilometers of sewer mains across the island.

The NWC’s operating expenses are paid for via user fees. “We don’t get support from the government,” says Barnett, “unless there’s a specific project that government wants us to do, then they will provide us with some capital resources, but, in general, the revenue we earn is what takes care of our operating expense and loan portfolio. In other words, we try to be as self-sufficient as possible.”

The National Water Commission of Jamaica operates within the policy context of the Government of Jamaica’s goal of universal access to potable water by the year 2025 and the establishment of sewerage systems in all major towns by 2020. This presents a serious challenge for the NWC because proper water supply and wastewater services are highly involved, complex, and costly – particularly in Jamaica where the need to pump water to and from remote areas over hilly terrain incurs very high electricity bills.

According to Barnett, Jamaica also suffers from a high amount of water loss, or what is known as non-revenue water (NRW). One reason is due to the country’s aging infrastructure and another is because of non-payment of bills and/or pilfering of water resources by segments of the population. “That is what we are now grappling with,” says Barnett, ruefully. “We have high physical losses in our network – we have infrastructure that is probably more than a hundred years old – coupled with the fact that we have dispersed communities that are socially and economically challenged, creating its own challenges for the enterprise to bill and collect for water that we produce and distribute in some of those areas.”

Regarding the NWC’s infrastructure, Barnett admits that the level of investment undertaken when it was first formed was far below what it should have been, based on the system’s expected utilization. “When we were established in 1980, there was no real capitalization of the enterprise to renew its assets,” he states. “And, therefore, we were only able to invest as the resources came available. So, investment in the early stage was very low. We did not invest as much as we should.”

Barnett believes that controlling water loss is one of the NWC’s main challenges, and that solving that problem will lower the agency’s costs, considerably. “I consider the reduction of water loss as a new supply,” he says. “Meaning, if I can reduce my losses from the water that I already produced and distributed, then I’ll be able to add more customers and encourage more development because more water is readily available. And the agency can become more efficient just by tackling one major problem. So, that is where my main focus is, because there is a direct correlation between high NRW and high energy costs.”

Barnett’s spotlight on saving money is based on his desire that the National Water Commission of Jamaica could become, someday, profitable enough to be a contributor to the government’s coffers. “We want to become a financially viable entity and be a net earner for the government,” he declares. He also likes to think about ways that the agency can expand its revenue stream, such as bottling water and competing with private sector companies in that arena. “Since our water has a more superior quality and taste than some that is already on the market,” he asserts. “So there are opportunities that we could look at. But first, the agency has to make sure that the supply of water is reliable and then we can venture into other areas and do those value-added projects.”

Meanwhile, Barnett insists that clean water, in and of itself, is still one of Jamaica’s most valuable “currencies,” and providing it to as many residents, businesses, and tourists, as possible, it is key for the country’s future growth. “Our vision is to contribute positively to national development,” he asserts. “We want to ensure that the residents have access to regular, high-quality, potable water, and secondly, we want to ensure that the services that we provide encourage investment in the various sectors that the government is targeting – tourism cannot flourish without a reliable supply of water; certain industries are unlikely to survive without a reliable source of water. So, we consider ourself the backbone of, if not the main ingredient for, national development, because water touches all spheres. Water is really what determines the health of the nation and the level of development that can take place in a country.”

And that is why the motto of Jamaica’s National Water Commission is “Serving You in so Many Ways.”

Check out this handpicked feature on National Properties Limited.

AT A GLANCE

WHO: The National Water Commission of Jamaica

WHAT: The main provider of potable water supply, and the collection, treatment and disposal of wastewater services in Jamaica

WHERE: Kingston, Jamaica

WEBSITE: www.nwcjamaica.com

PREFERRED VENDORS

Hood-Daniel Well Company Ltd. – www.hooddaniel.com

Caribbean Maritime Institute – www.cmi.edu.jm

This information will never be shared to third parties

This information will never be shared to third parties